THE

HOUSE OF GOVERNORS

by

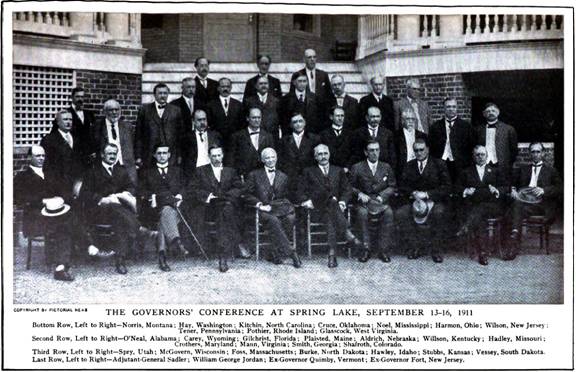

William George Jordan

he

atmosphere of political thought in the nation today is permeated with restless

rebellion of protest against the growing centralization at Washington.

Rumblings of revolt in the public press are becoming louder and more

unmistakable, and political leaders are furbishing the dingy armor of States

rights in preparation for battle. The usurping by the government of the

lawmaking power of the States is declared to be a forsaking of the great

principle of democracy, the rock upon which the fathers founded the Republic.

The Federal Government, following the spirit of the age,

is itself becoming a trust—a great governing trust, crowding out, and

threatening openly still further to crowd out, the States, the small jobbers in

legislation. As the wealth of the nation is concentrating in the hands of the

few, so is the guidance of the destinies of the American people becoming vested

in the firm, tense fingers of a small legislative syndicate.

The nation soon will be no longer a solid impregnable pyramid, standing on the

broad, firm safe base of the united action of a united people, but a pyramid

dangerously balanced on its apex—the uncertain wisdom of a few.

There is a growing realization percolating through the

varied strata of politics down to the man in the street that the new centralization

is a menace. It is a menace. It is not in harmony with the spirit of the

Constitution, its very essence, though it may be in

no technical disaccord with its letter. Had the invasion of the self-governing

rights of the States been manifested in evil laws forced into being through a

dominated Congress the whole country would have risen to meet the issue at

once, but it has come with needed legislation, wise provisions and vital

issues, and because of the guise it is all the more dangerous because more

insidious. The government of the founders was fraternal; the new government

threatens to become paternal.

Were the dictates of any centralized administration

inspired with the absolute wisdom of omniscience and executed with the

relentless certainty of omnipotence, with every microscopic phase of every act

consecrated to the best and highest good of the whole country it would still be

a menace. It is establishing a dangerous precedent—it is placing the

self-governing power of the States in pawn with the Federal Government, with

the chances of the ticket becoming lost or the interest rate being raised or

some other technicality occurring that might make redemption difficult or even

impossible. The mantle of infallibility of one administration may not drop

serenely of the shoulders of its successor—wisdom, exalted ideals, and broad,

unselfish statesmanship are not always hereditary in office.

This centralization has not been the work of one administration. It has been evolving for years. During the present term it has merely assumed a more vivid, picturesque, startling phase, sufficiently distinct to be portentous, but this centralization is natural and under past conditions inevitable. If there is today Federal

usurpation of States rights it is so merely because the States

have largely abrogated their rights through disuse—through lack of proper exercise. The States themselves

have been

to blame. Unless they may

become irremediable, and America will then be but an autocracy under the false guise

of a democracy.

Reference to the constitution will show the privileges the

people have been, perhaps unconsciously, surrendering. The Constitution clearly

defines the powers of the Federal Government in all its branches. The ninth

amendment says: “The enumeration in the

Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage

others retained by the people.” The tenth amendment says: “The powers not delegated to the United

States by the Constitution nor prohibited by it to the States are reserved to

the States respectively, or to the people.” Here was the States’ warrant

for action, yet corruption and mismanagement had grown brazen, graft

flourished, arrogant dominations of trusts became more reckless, illegal

aggregations of wealth towered higher in their insolence, bribing of

legislators grew more flagrant, patriotism and loyalty were continuously

sacrificed on the altar of politics—these and a dozen similar evils, sapping

the life of the Republic, were not met by the States when they had the

opportunity in their hands.

A few States really did show vitality and virility and

earnestly sought to meet the evils, failing to a degree in their efforts by the

largeness of their task and the lack of co-operation from their sister States.

The situation grew desperate. Then came a Federal administration with nerve,

courage and resoluteness, and sought seriously to begin to solve the problem—to

save the situation.

If the administration went beyond its rights, if it for a

time trespassed on States rights, it was because the States were culpably

negligent and in active. If there is a fire smoking in the hold of an ocean

steamer and the captain and crew fold their arms in complacent inactivity,

hoping the fire will die out, it is the duty of the passengers or any of them

to head and organize a bucket corps to stifle the flames. But when it is all

over and the captain and crew waken to the realization of their dereliction and

learn their lesson they would be foolish to let this emergency corps run the ship.

Have the States learned their lesson and awakened to their duty or will they

continue to let centralization govern the ship of States?

The trusts for years had been growing more colossal,

aggressive, and law-defying. The press of the nation chronicled the details,

kept hammering at real evils, seeking to rouse legislation. The people talked

of it with a sense of abject hopelessness as if an earthquake

were coming and they saw no escape. There was unending talk as

monotonous as a phonograph, with practically as little results. The States as a

whole did little or nothing, Then the Government

passed the Anti-Trust Law, the thin edge of the wedge of broadening

legislation.

The iniquitous rebates of the railroads, that forced

thousands of small dealers into bankruptcy and restrained commerce and the

natural development of individual interests, continued for decades practically,

if not actually, untouched by the hand of State law. The States could have met

the evil, partially at least, but they did nothing. Then the Government passed

the rate bill.

Grasping capital, holding nothing sacred, not even the

food of babes, carried adulteration and food poisoning to a point where it

seemed that the only way to live was to give up eating. The newspapers exposed

it, the magazines exploited it, scientists lectured on it, societies were

formed to fight it, but the States waited—for the Federal Government to pass

the Pure Food Law.

The President and the Secretary of State have declared

repeatedly that the States are not able to unite in the making of laws on

questions of national importance and that therefore the power to make these

laws must become vested in the Federal Government. With all due deference,

however, may it not be asked whether the failure of the States to make uniform

legislation has not been due to the lack of any method of the States to get

together in conference as States? Were this provided wherein is it impossible

for the States themselves to handle this legislation? That there are

difficulties is self-evident; that these difficulties are insurmountable is

open to question. Should not any plan that has within it a germ of hope be

tried, if the trying imply no danger to the fullest

safety of the Union, before we hopelessly accept as a finality the imputation

that the States are no longer fit for self-government? Secretary Root not only

says that “these things the States no longer do adequately,” but also that they

(the States) are no longer capable of adequately performing." The

Honorable Secretary conjugates the impotence of the States in the present and

the future tense.

There does seem to be one simple, practicable method yet

untried which the writer desires here to propose—one that is in such perfect

harmony with the letter and the spirit of the Constitution that it would

require no constitutional amendment; one that might not even require (for an

initial trial, at least) legislative action in any State; one that upsets no

established order in the conduct of the nation; one that would bring the States

into closer unity and harmony without lessening in any degree loyalty and

allegiance to the Federal Government; in short, a plan that if worked out

successfully in practice would put the rights of the States on a firm,

recognized basis and make centralization forever an impossibility in the

American Republic. The plan which I wish here humbly and respectfully to

present to the leaders in the political activities of the country, to our

Governors and legislators, and to the American press and public is the organization

of

The

House Of Governors.

It is

proposed that the Governors of the forty-five States meet annually for a

session of two to three weeks to discuss, consult and confer on vital questions

affecting the welfare of the States, the unifying of State laws and the closer

unity of the States as a nation. The House of Governors would have no lawmaking

power, nor' should it ever aspire to such power. Its force would be in

initiative, in inspiration and in influence. The Governors would seek to unite

on a general basis of action on great questions to be submitted to the

legislatures of the respective States in the Governors' messages. It would seem

that an august, dignified body of forty-five Governors, representing their

States, with the lawmaking power of forty-five legislatures behind them, should

in time become an inherent part in the American idea of self-government and a

powerful factor for good in the nation.

This brief statement covers the broad lines of the suggestion

and for it we ask consideration in the thought that follows this outline.

In the Congress of the United States, the Senators, chosen

as they are by the State legislatures, nominally represent their States, but

not the people of their States, for the latter have no

direct voice in their selection. The members of the House of Representatives do

not represent their States, but simply districts of their States. With ties to

their constituents and with duties and obligations to them they may in theory

have the interest of the entire State as a matter of paramount importance in

their hearts, but in fact they never lose sight of the finality of value in the

Congressional district. The Governor of the State, however, is elected by the

people, is directly responsible to the people, and is in constant touch with

the people, keeping his fingers close-pressed on the pulse of their needs and

problems. The voice of the Governors, therefore, in the proposed new house

means a new, direct, vital representation of the people in the affairs of the

State, and in the harmony of the States making up the nation, such as the

people have never yet had in the life of the Republic.

On many great questions it is difficult to secure national

legislation and on others it is impossible to secure it without constitutional

amendment. Today we have no national holiday legalized by Congress for the

States—not even the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving Day or Christmas—yet by the

action of the separate States these days are universally observed. They are

national in scope, but not national in genesis; so if the legislatures of the

forty-five States, working together through the House of Governors for uniform

laws, should pass the same law the practical effect of a national law would be

secured without Federal action.

In the House of Governors no majority vote should be

binding on the minority. Should even forty-four members of the House in full

session agree, the one member not concurring should have absolute freedom of

action and he or his successor would probably join the majority side at the

next session of the House. The House should determine by vote the ratio of the

members present that is to be considered the minimum requisite for the initial

impulse for action toward uniform State legislation throughout the country on

the specific question. Should the number of votes be below the ratio set as a

basis of unity the matter could go over to the next session for reconsideration.

If on the subject of, let US say, divorce, twenty-five

members of the House were to agree on a general plan the twenty-five Governors

thus concurring would suggest to their respective legislators in their ensuing

messages the passage of a bill in accordance with the recommendation. The

legislatures, of course, would have absolute freedom to pass it or not as they

deemed best, but the recommendation would have a greater dynamic effect and a

stronger moral influence when each legislature knows that twenty-four other

legislatures are considering the same proposed law. Let us assume that of the

twenty-five States eighteen passed this bill, in the other seven were public

sentiment sufficiently aroused and the people sufficiently united, this

question might be made an issue in the next campaign and those legislators

elected who would be pledged to carry through the bill.

At the next meeting of the House, with the prestige of the

adoption of the law by eighteen States, ten new converts might be made among

the Governors non-concurring in the first session, and so in the course of a

few sessions we might have uniform State legislation on this vital problem

without Federal action. A law thus finally passed by all of the States would

more truly represent the sentiment of the American people than any law passed

by the Federal Government, even if constitutional amendment or new revised

interpretation of the Constitution empowered the passing of the law.

The annual meeting of such an able deliberative body as

the House of Governors would receive careful attention from the press of the country.

Every State being represented by its Governor, and the problems discussed being

vital ones, there would be secured throughout the country simultaneous

'consideration of the questions before the House, a thorough, practical

ventilation of the subjects and a general study of the proposed remedies. Vague

diffused public opinion, through the influence of the House of Governors, would

be crystallized into public sentiment, and this sentiment, the people's voice,

could compel legislation. The general opinion of the people of this country

today, it would seem, is against capital punishment—a sad relic of primitive

barbarism still persisting with war in this vaunted twentieth century

civilization—yet there is no method today by which this unexpressed public opinion

can be vitalized, transmuted into public sentiment manifesting itself in

uniform State laws, yet the House of Governors might accomplish it as part of

the work of a single session.

The lack of uniformity in State legislation today is so

clearly recognized as an evil in our political system that further details in

this article seem unnecessary. Any plan that even faintly foreshadows the

possibility of bringing order out of this chaos of complexity and contradiction

would seem worthy of real1y serious consideration.

The House of Governors seems to offer no chance for graft,

col1usion, combination, pairing off, the working of private interests, bribery,

jobbery, corruption or any of the other diseases to which legislative bodies

are liable. This immunity arises from the non-lawmaking character of the House.

It is said to be easier to buy State legislatures than to purchase Federal

action or Federal inactivity. The House would thus have the dignity, character

and poise of the Federal Government. The Governors here would be subject to no

pressure, they would not be likely to be carried off their feet by the

whirlwind eloquence of one of their members advocating some Utopian scheme or

some trust measure masquerading as a plan of public benevolence. But even if

temporarily captivated they would probably cool on reflection, and there is no

chance of the goldbrick fallacy proposed being able to stand the acid test of

wide public discussion by press and people and to pass the safeguarding process

of forty-five legislators.

It seems advisable that the meetings of the House of

Governors should be annual, though the sessions of State legislators are annual

in only six of the States, while quadrennial in one and biennial in

thirty-eight. In 1907 only six States have legislative sessions, but in 1908

forty-one States—or all but Alabama, Oregon, Virginia and Wyoming—hold

sessions. Were the House of Governors to meet during the present year a

splendid test of the value of their session could be made in January, 1908, all

the forty-one State Legislatures then meeting, except Florida (April),

Louisiana (May), Georgia (June) and Vermont (October).

It may be objected that the Governors could not spare time

away from their official duties to attend sessions of the House, but as their

bodily presence at home is not necessary except when the Legislature meets,

this objection is more theoretic than real, and the State could for a term of

two or three weeks be left to the Lieutenant-Governor or to the Secretary of

State as Acting Governor.

The place of meeting of the House of Governors should not

be in Washington, D.C. (except possibly its first session), but successively in

State capitals selected by vote of the House or by the decision of a committee,

and giving the honor of the session successively to States in rotation on a

general plan of choice, selecting for the first year perhaps an Eastern State,

the following year a Western State, then a Northern, then a Southern and last a

Central State, repeating the order of choice till the forty-five (Oklahoma, the

forty-sixth, not having been officially admitted to the Union at this writing),

shall have been recognized.

The date of the session should be at a season that would

avoid the time of the sitting of the State Legislatures and the months directly

preceding the November elections. The cost of the meetings of the House of

Governors should be little more to each State than the traveling and other

necessary personal expenses of its Governor for the brief period of the

session. Any State selected for an annual meeting would gladly provide its

legislative assembly room for the meetings of the House, with accommodations

therein for visitors (perhaps by invitation) and press representatives at the

daily sessions. The force of doorkeepers, pages, stenographers and others

needed for the brief term should be but a slight tax on the hospitality of the

State.

In order that the members of the House of Governors should

be fully informed in advance of the topics to be discussed and to save valuable

time for the session it is suggested that it shall be the duty of the chairman

of the House or of the committee appointed therefore to invite the members, say

four months before the session to send in lists of suggestions of vital topics

for consideration. These lists when received from all Governors would be

tabulated in the order of their importance and submitted as candidates of

topics. The Governors would then mark a given number of subjects, a number in

excess of those likely to be covered during the session, and from these lists

of preferences returned to the chairman, or committee, the resultant official

list of elected subjects would then be sent to each member, thus giving him

time for thoughtful preparation for the session, and enable the House to take

up its programme of work, with no loss of time,

immediately after electing the necessary officers.

Among the subjects of vital interest to the entire country

and on which free discussion tending toward uniform legislation is desirable

may be named: marriage and divorce, rights of married women, corporations and

trusts, insurance, child labor, capital punishment, direct primaries, convict

labor, prison reform, contracts, income tax, mortgages, referendum, election

reforms and similar topics. The House of Governors might have a consulting

board of legal advisers, specialists in constitutional law and Federal and

State legislation, if such counsel were needed.

On every important question brought before the House it

would be found that some one or two States had progressed further than others

in some direction. Each State working out its own problem has to a degree

specialized, as Oregon with its referendum, by which the people direct their

legislators and by which party machines have been abolished. Those States that

have partially solved great problems in self-government have valuable material

in the form of documents, reports, discussions, blue books, records, etc.,

giving in concrete form the results of their experiments and experiences which

would be inspiring to Governors desiring to look into these questions with the

fullest light possible at the psychologic moment of

deep personal interest.

We have, annually, conventions of educators, of lawyers,

of ministers, of doctors, of scientists and of members of every profession,

trade and industry, meeting to become acquainted, to confer on matters of

common interest and to strike the fire of new wisdom or inspiration from mutual

contact, yet two State Governors may never meet except accidentally or incidentally

at some dinner or political gathering. The newspapers report even these

meetings only because of the opportunity they afford to spring again on the

public a worn-out epigrammatic colloquy between two Southern Governors on the

subject of thirst.

The Congress of the United States would in no wise be

disturbed in its normal work as marked out for it by the Constitution by the

institution of the House of Governors. There need be no conflict between

Congress' and the new House, for the States, quietly working out their own

problems by the light of their united wisdom, could not trespass on the

specific legislation left by the constitution to the sole and absolute charge

of the Federal Government.

The House of Governors, even if it were merely a

meeting-place for the heads of our State governments, would be of value, but

with regular conferences on the broad basis of mutual helpfulness in the

unifying of our laws and of combined action in staying the insidious invasion

of centralized government, with the sympathy and co-operation of the people of

the country and with the lawmaking powers of the State legislatures led into

harmony, shamed into activity, or forced to do the people's will, the House of

Governors, it would seem, should become in a few years a mighty force in the

American Government. It should give the people greater power, strengthen the

States by granting them fuller liberty, unite and unify them more perfectly and

make the United States more truly the United States.

We need in our country today less politics and more

statesmanship, less party and more patriotism. We need an awakening to higher

ideals. We need a higher conception of America's place and destiny in the

evolution of the world. We need something nobler as a purpose than our

self-satisfied complacency at the material prosperity of the nation, for there

is a moral and ethical success that is never rung up on a cash-register. We

need the scourging of the money changers out of the temple of legislation—State

and national. We need a purifying and ennobling of the body politic. We need

the clear clarion voice a great inspiration to rouse the States to their

duty—not the gilded phrases of mere rhetoric, but the honest eloquence of a

high and exalted purpose like that ringing speech of Patrick Henry's, a century

and a quarter ago, which breathes the very spirit of the present hour of need

when it is said that the States are too weak to do their duty and must

surrender to government centralization:

“They tell us that we are weak, unable to cope with so

formidable an adversary. But when will we be stronger? Will it be the next week

or the next year? Shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? Shall

we acquire the means of effectual resistance by lying supinely on our backs and

hugging the delusive phantom of hope until our enemies shall have bound us hand

and foot? Sir we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the

God of nature has put into our power.”

Whatever tends to lessen the right of the American people

to be absolutely self-governing, whatever tends to take from eighty million

people their privileges and to hypothecate them in the hands of a few, is a

menace in principle, hazardous in what it portends and in what it makes

possible.

The plan of the House of Governors is simple, seemingly

feasible, cannot possibly do harm and may have within it the germ of great

good. Is it not worth a trial?